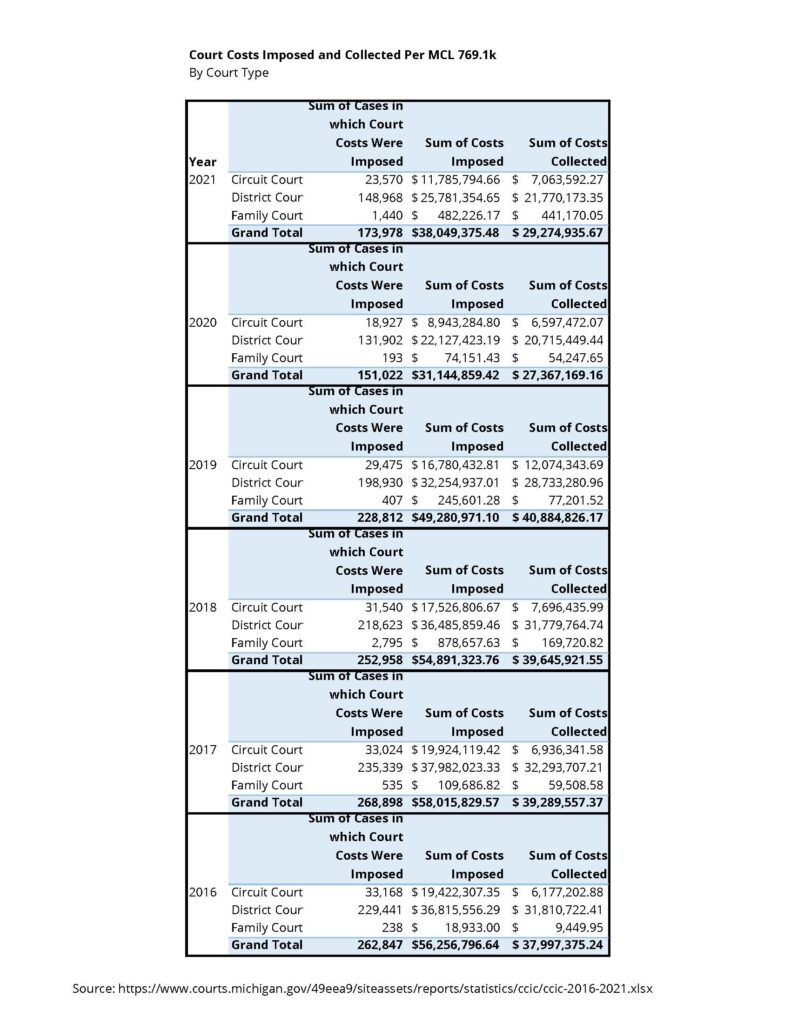

Most Michigan trial courts assess and collect local court costs in criminal cases as allowed by MCL 769.1k.

Over $29 million was collected in 2021. Some counties collected a few thousand dollars. Others receipted a couple of million. The collected money stays with the local government treasury (or funding unit).

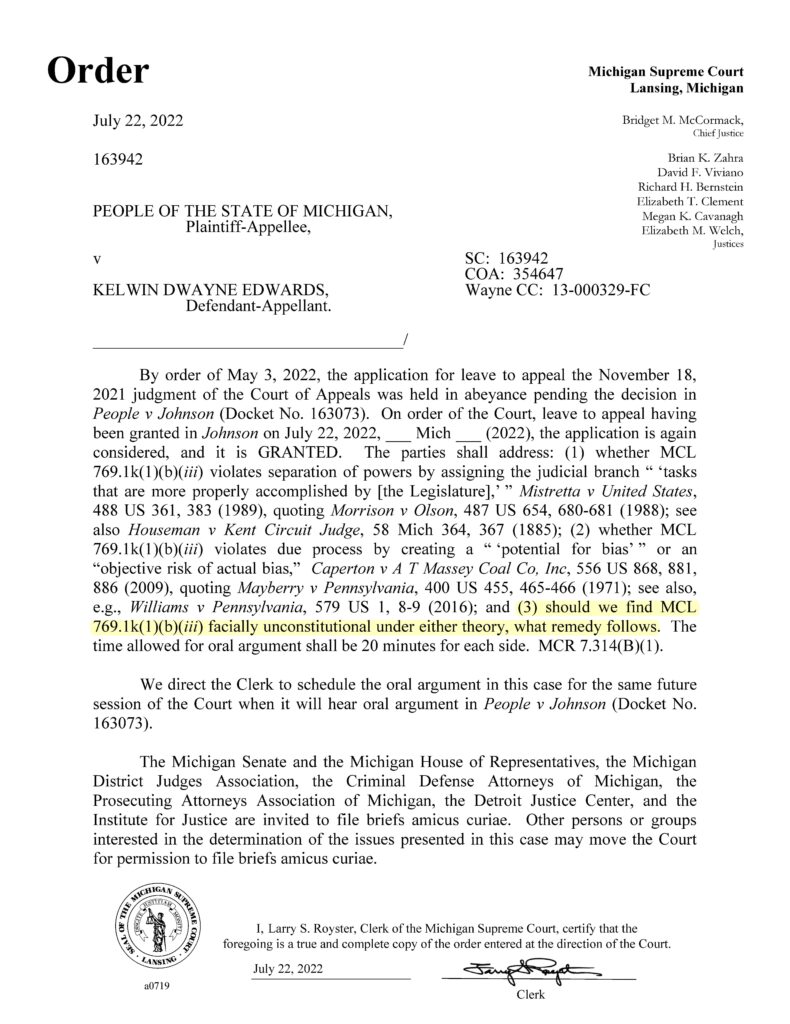

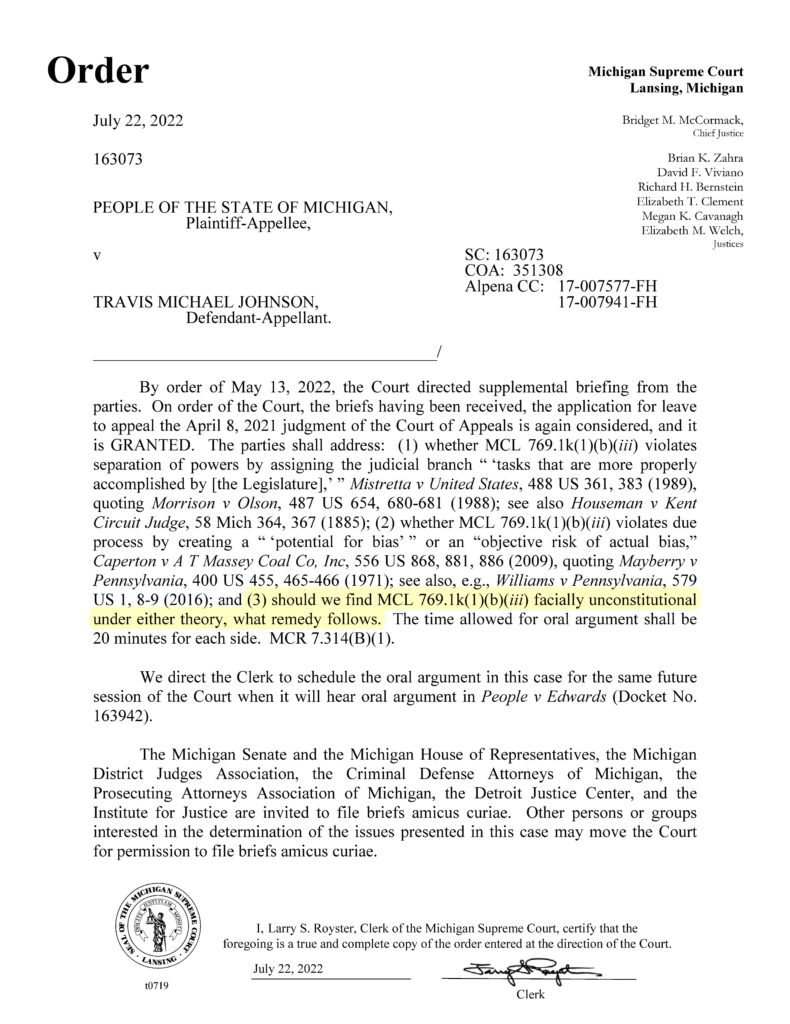

But things could change when the Michigan Supreme Court considers People v Travis Michael Johnson (163073) and People v Kelwin Dwayne Edwards (163942) during its 2022-2023 term and decides whether those costs are facially constitutional.

If things do change on the costs front, the Michigan Supreme Court now invites briefing on how that should look:

(3) should we find MCL 769.1k(1)(b)(iii) facially unconstitutional under either theory, what remedy follows.

What makes this a big deal?

163073 is an Alpena County appeal. 163942 is from Wayne County.

Behind 163073 are another 16 or so abeyed appeals from cases starting in Oakland, Ionia, Chippewa, Crawford, Jackson, Livingston, Washtenaw, Kent, and Macomb counties. No doubt this is a statewide issue.

Curious for a data-nerd detour?

Here are alternate links to the 2016-2021 court-costs data compiled by the State Court Administrative Office:

- [Uploaded as a GoogleSheet] https://bit.ly/3cDBqnG

- [Direct Excel download] https://www.courts.michigan.gov/49eea9/siteassets/reports/statistics/ccic/ccic-2016-2021.xlsx

I can hear you now. “Wait! Didn’t the Michigan Supreme Court already hear argument in People v Johnson (163073)?”

Yes! It did in April.

And after the mini-oral argument on the application (MOAA), the Court ordered the parties to address three questions including this court-administration delight:

(3) should we find MCL 769.1k(1)(b)(iii) facially unconstitutional under either theory, what remedy follows.

After considering the parties’ post-argument written responses, last week the Michigan Supreme Court granted leave to appeal, added another case (Edwards), and invited amicus briefing from other groups. Again, the Court asks:

(3) should we find MCL 769.1k(1)(b)(iii) facially unconstitutional under either theory, what remedy follows.

One way to look at the Court’s briefing/argument order as for Q3: Now what are trial courts supposed to do on the earlier files?

Imagine that any Michigan trial court already assessed a fine and court costs but—next term—the Michigan Supreme Court sees this cost-assessment provision and practice as unconstitutional. Facially.

What are Michigan’s trial courts to do with that hot potato? What “remedy” are trial courts supposed to carry out?

That is one way to look at Michigan’s high-court question. (Okay, okay, that’s how I read it.)

“Don’t assess that cost in future cases” is an easy response.

“Easy” is also suggesting: For the named defendants, issue a remand order for the trial court to modify the judgment of sentence by voiding the unconstitutional cost and voiding any original cost payments already processed by the trial court, and issue a refund within 45 days. Similarly: Modify any active wage assignment orders or orders to remit prisoner funds.

But what about the thousands of other active trial court files where there already was a (hypothetically unconstitutional) local court cost assessment and it remains unpaid?

Partially unpaid? In warrant status? (Spoiler alert: This is how constructive, frontline trial court staff meetings can play out when they are held.)

What should happen with all of the other files in the other courts? What remedy should follow?

If other court files will be financially adjusted, independent auditors will want a justifying companion order. Michigan’s Trial Court Financial Management Guidelines also require employees to enter a reason for adjusting financial records in any case management system. [Section 6-05(C)(6)]

So what should a plain-language and global administrative order from the Michigan Supreme Court authorize?

Should all trial courts be administratively ordered to review their files and make financial adjustments?

Should there be financial adjustments on files that were paid, closed, and no appeal was filed? And even if not, should any supreme court order still mention that point with the goal of proactively increasing litigant and public understanding? (For the love of all that is good, give trial court staff and managers a higher and clearly understood directive to point to.)

Would it be helpful for the supreme court order to say what the trial courts are supposed to do and volunteer what the trial courts cannot do so that public expectations are better managed? Like non-lawyer Brené Brown counsels: Clear is kind. Unclear is unkind.

If a defendant is owed a refund on a partial payment but has an outstanding balance on other fines/fees assessments, does the trial court process a direct refund to the defendant or simply void the earlier partial payment and re-apply it to the other valid but still unpaid assessments?

What if a 20% late fee (MCL 600.4803) was added to the unpaid assessment? Should the late fee be removed on top of any unpaid unconstitutional assessment? Cashiers and clerks do not enjoy that type of decision-making discretion; they need a court order. The higher, the better!

What if a credit or debit card convenience fee was added to an earlier partial payment made on the now-unconstitutional assessment? Money order or cashier check costs? Would any type of “costs-plus” refund from the trial court be possible?

Should any repayment from a trial court include interest? Is that possible? Amount?

Who is owed any refund if a partial payment came from an applied bond that was posted by a third party? Should that bond variable matter? (I do not think it should but I can imagine many telephone and front counter conversations/debates with trial-court staff about it.)

When does any remedy become “effective” and what is the deadline for trial courts to fully implement it?

Should completion be reported to SCAO?

If refunds are owed and when the proper payee cannot be identified or located, can the unclaimed funds remain with the funding unit or must they be escheated to the State of Michigan as unclaimed property?

Trial court leaders and staff will probably noodle other excellent implementation questions.

No doubt, the Michigan Supreme Court may eventually decide that responses to its third question do not have to be considered. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Michigan’s Gilda Radner probably described it best should that route happen:

But until that moment is ever reached—whew!—a lot remains in play.

$29+ million annual cash flow spread throughout the state is not trivial. The prospect of partially undoing it invites thoughtful questions.

Am looking forward to seeing how things unfold from question three on the Court’s leave granted briefing/argument orders. Will advocates and interested parties embrace this unicorn opportunity?

Make no mistake: What remedy follows is procedurally conditioned on a gigantic “if”.

Even so, getting there could prove to be positively fascinating.