The public, litigants, media, and legal community have good reason (indeed, an obligation) to pay attention to what’s argued and decided in their state supreme courts.

State courts are the only forum for enforcing a right under their own constitutions when the Supreme Court of the United States does not, reminds federal judge Jeffrey S. Sutton in 51 Imperfect Solutions: States and the Making of American Constitutional Law.

Fortunately, today is easier for many to “attend” their state high court arguments without ever having to travel to and sit in the grand halls of justice—thanks to technology and a COVID-19-supercharged effort to remote justice.

And to their credit, many high courts stream their hearings (either video, audio, or through an arrangement with public television) when the cases are argued. [Alabama, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and South Dakota do not.]

But not every interested person is available to watch or listen as the cases are argued. So it’s important to think about the public’s accessibility to their high court’s oral argument work product even after the case is submitted for private deliberation.

This post looks into that zone of post-oral argument, public accessibility.

The declining numbers

34 (states and the District of Columbia’s highest court) keep their videos online—post-argument—for 24/7 public access.

Of those, only 23 apply subtitles (or captions) to the video arguments. Why does that matter? Videos are accessible for those with hearing loss when they include correct subtitles. No subtitles = no access for them to witness and understand that part of the court’s work.

Earlier this month, the World Health Organization declared hearing loss a world health crisis, and they published a report.

Fullscreen Mode“The COVID-19 pandemic has underlined the importance of hearing. As we have struggled to maintain social contact and remain connected to family, friends and colleagues, we have relied on being able to hear them more than ever before. It has also taught us a hard lesson, that health is not a luxury item, but the foundation of social, economic and political development.”

Those with limited-English proficiency and English-language learners also appreciate captioned videos to improve comprehension and fluency. Captioning benefits many.

Accuracy = access to justice

But only seven state high courts—seven!!—edit their video captions to ensure accuracy.

Applause and appreciation to Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Ohio. (Separate hat-tip to New York for preparing official written transcripts, even though they’re not posted within the archived videos. The Supreme Court of the United States also prepares and posts official written transcripts from its oral arguments.)

16 state high courts apply unedited AI-generated captions to their online videos. These are often inaccurate. Many are hosted on YouTube and YouTube warns:

Captions are a great way to make content accessible for viewers. YouTube can use speech recognition technology to automatically create captions for your videos.

Note: These automatic captions are generated by machine learning algorithms, so the quality of the captions may vary. We encourage creators to add professional captions first. YouTube is constantly improving its speech recognition technology. However, automatic captions might misrepresent the spoken content due to mispronunciations, accents, dialects, or background noise. You should always review automatic captions and edit any parts that haven’t been properly

To see why AI-generated captions should be treated as the “first draft” and not the final submission, try watching and following this unedited, AI-captioned oral argument. The audio has been removed.

It’s not easy, is it?

Unedited, AI-generated subtitles undermine public understanding of a court’s work, disenfranchise certain groups, and erode confidence in the court.

The practice of applying AI-generated subtitles, without editing, ignores the perspective and functional access needs of interested persons who depend on accurate subtitles.

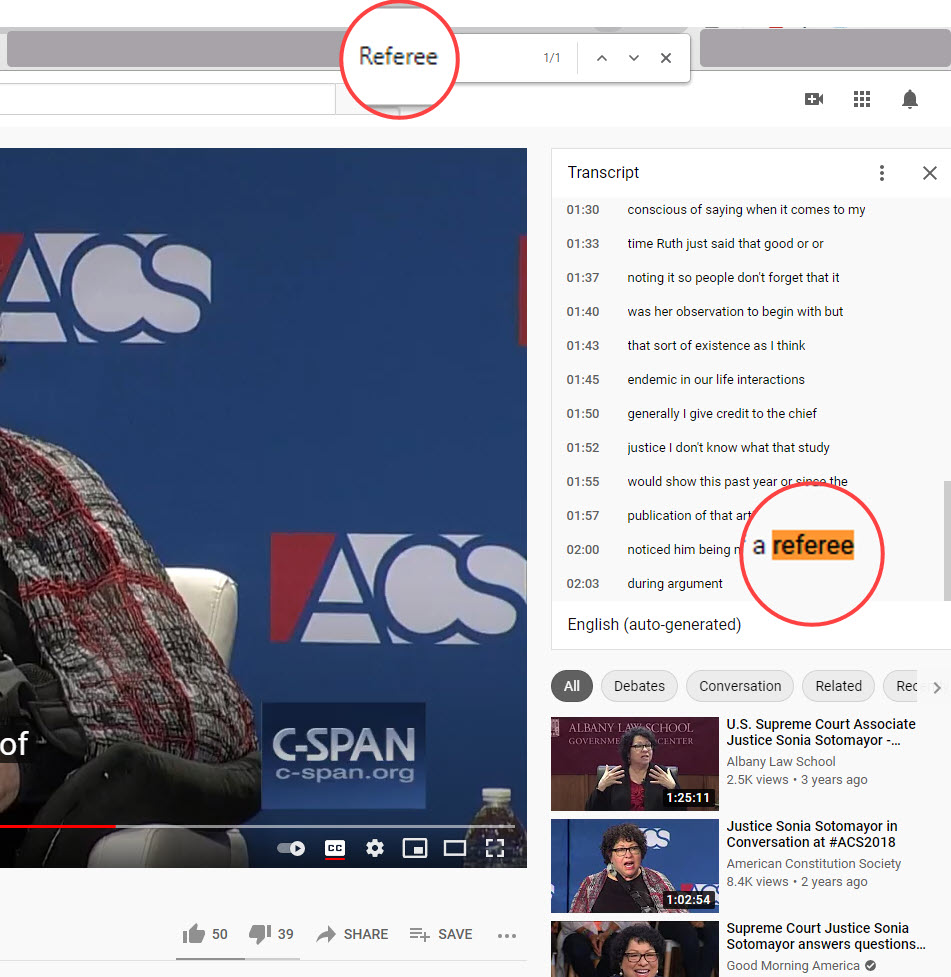

When the caption displays, “mr wassusha” how is someone with hearing loss supposed to know that the speaker really said, “Mr. Restuccia”? Names and important legal terms are often mangled. Watch some examples from the captioned-only video:

Here’s another problem. Unedited subtitles are a silent banner advertisement of an organization’s indifference. Consider what can follow:

- Prospective employees who either are or support disabled persons become disenfranchised and self-opt to not even seek employment at that court. The court tragically misses the chance for diversity contributions in their day-to-day operations, particularly when working on inclusive-design projects.

- Compromised perception of procedural fairness can introduce another concern that courts should be sensitive about. If a court doesn’t edit their argument subtitles, imagine how a litigant will feel about their chances for a fair outcome in a case that’s about an employer, government body, or business that did not make an accommodation required by law? Probably not very good.

What are the editing standards? Are there any?

The great news is that the fix is uncomplicated, and it doesn’t have to be expensive!

Even though the Federal Communications Commission standards do not apply to non-television broadcast judicial videos, those regulations can be helpful for judicial workflow best practices.

Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Ohio’s edited captions seem to follow 47 CFR § 79.1(j)’s criteria for accurate, synchronous, complete, and appropriately placed captioning:

(i) Accuracy. Captioning shall match the spoken words (or song lyrics when provided on the audio track) in their original language (English or Spanish), in the order spoken, without substituting words for proper names and places, and without paraphrasing, except to the extent that paraphrasing is necessary to resolve any time constraints. Captions shall contain proper spelling (including appropriate homophones), appropriate punctuation and capitalization, correct tense and use of singular or plural forms, and accurate representation of numbers with appropriate symbols or words. If slang or grammatical errors are intentionally used in a program’s dialogue, they shall be mirrored in the captions. Captioning shall provide nonverbal information that is not observable, such as the identity of speakers, the existence of music (whether or not there are also lyrics to be captioned), sound effects, and audience reaction, to the greatest extent possible, given the nature of the program. Captions shall be legible, with appropriate spacing between words for readability.

(ii) Synchronicity. Captioning shall coincide with the corresponding spoken words and sounds to the greatest extent possible, given the type of the programming. Captions shall begin to appear at the time that the corresponding speech or sounds begin and end approximately when the speech or sounds end. Captions shall be displayed on the screen at a speed that permits them to be read by viewers.

(iii) Completeness. Captioning shall run from the beginning to the end of the program, to the fullest extent possible.

(iv) Placement. Captioning shall be viewable and shall not block other important visual content on the screen, including, but not limited to, character faces, featured text (e.g., weather or other news updates, graphics and credits), and other information that is essential to understanding a program’s content when the closed captioning feature is activated. Caption font shall be sized appropriately for legibility. Lines of caption shall not overlap one another and captions shall be adequately positioned so that they do not run off the edge of the video screen.

Anything else to support the practice of using edited subtitles?

Yes! The Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) and Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA) encourage courts to implement technology that’s designed to meet the needs of all users. This includes ensuring disability accessibility and reducing barriers for those with limited-English proficiency.

Fullscreen ModeIn the end, courts have an inherent duty to the public, litigants, media, and bar to ensure that self-published information is accurate and reliable.

Fair enough. How easily can captions be edited?

I have had a quite easy time using Otter.ai. (This isn’t a product endorsement.)

I bought a flat-fee subscription ($30/month) for unlimited files. Imported an argument video to the Otter.ai website and a draft transcript (with timestamps) was processed and available in short order. A 62-minute video took 32 minutes to process.

I edited the text online—mostly adding speaker names and cleaning up text.

Text edited using Otter.ai can be exported to multiple formats: .txt, .docx, .pdf, and .srt. That last format is key for video subtitles. YouTube supports uploading .srt files and applying those captions to your video. It’s straightforward.

Off-topic but another helpful Otter.ai feature: The ability to “Export audio” to .mp3 files.

Who’s interested in audio-only oral argument files? Those who want to download and listen to them like they do podcasts or audiobooks.

Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, Ohio, Virginia, and Washington supreme courts post downloadable audio oral argument files. (And so does the Supreme Court of the United States.) Vermont makes them available through a Soundcloud player.

Another benefit of edited subtitles for everyone: Searchable transcripts!

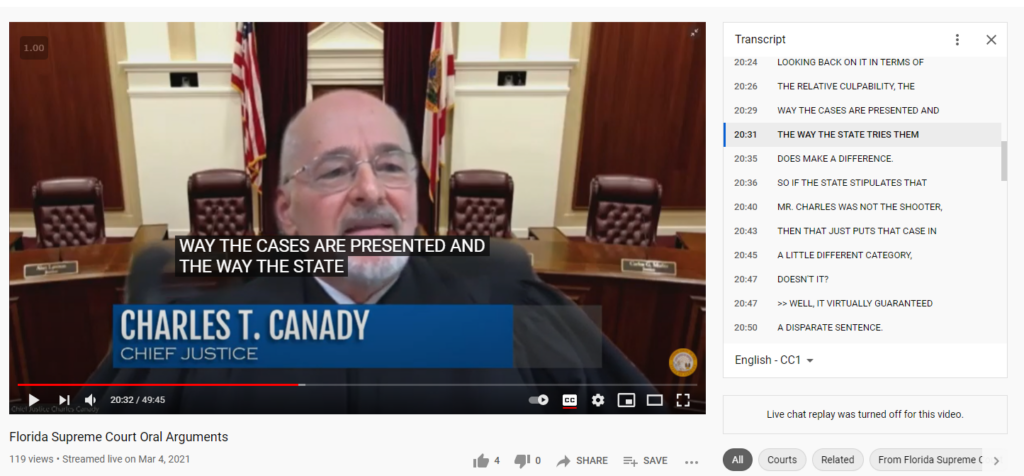

Did you know that you can view a YouTube-subtitled transcript as the video plays if you’re watching the video from your desktop?

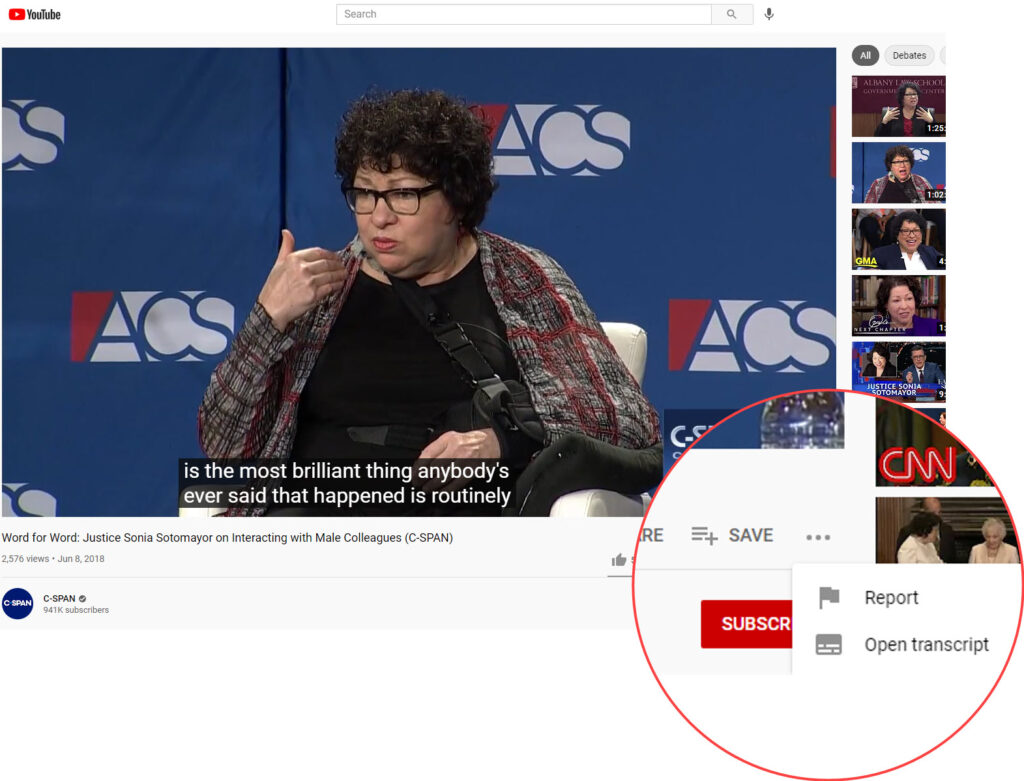

Below a YouTube video, select the three-dot icon […] to the right of “SAVE” and select “Open transcript.”

The entire time-stamped transcript opens to the right of the video. (Bummer alert: The open-transcript option is unavailable from mobile devices.)

Now place your cursor on the opened transcript and make your 🅲🆃🆁🅻 + 🅵 (or Command F for Macs) move. Open-transcript searching is a super-power timesaver when you want to zero into the key part of a video without having to watch the entire thing.

But, see, here’s the spoiler alert: The feature is of no value when a transcript is inaccurate and unreliable.

We didn’t need another reason to embrace accurate and edited subtitles in our videos. But searchability is a great one!

AI subtitles aren’t good enough on their own. On the positive side, it’s uncomplicated and inexpensive to make the subtitles better for everyone’s benefit.

Motivated by increased accessibility and inclusiveness, the benefits of transcript searchability, and improved procedural fairness, hopefully, more courts will welcome and embrace the chance to use edited subtitles.

Here’s a separate fun fact from across the pond. The regulatory body for UK television broadcasting released a study in 2006 to better understand how many people use subtitles and the subtitle usage by folks who have hearing loss. What did they learn? 18% of the population use closed captions—and 80% of those did not have hearing loss. Study participants without hearing loss explained that they used subtitles because they were very effective in making the programs understood.” Observations from others following that study:

- Viewers who know English as a second language benefit from closed captions, because they make it easier to follow along with the speech.

- Closed captions help with comprehension of dialogue that is spoken very quickly, with accents, mumbling, or background noise.

- A video that mentions full names, brand names, or technical terminology provides clarity for the viewer.

- Closed captions help maintain concentration, which can provide a better experience for viewers with learning disabilities, attention deficits, or autism.

- Online videos with subtitles enjoy higher user engagement and better user experience

- Captions allow viewers to watch videos in sound-sensitive environments, like offices and libraries.