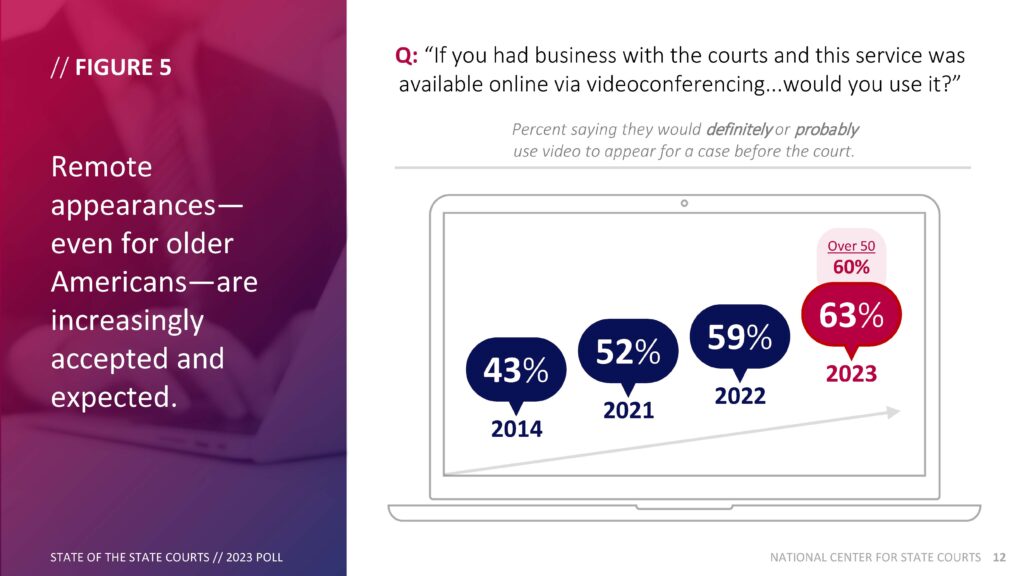

From the National Center for State Courts 2023 State of the State Courts annual public survey, we learned that a growing percentage of Americans—even older ones—would definitely or probably use video to appear for a case before the court.

The published 2021 findings, best practices, and recommendations from Michigan Trial Courts: Lessons Learned from the Pandemic of 2020-2021 detailed positive survey results from Michigan attorneys, courts, and users about remote access at page 29:

Of nearly 1,500 attorneys surveyed, 82 percent stated they want Zoom® hearings to continue after the pandemic.

The attorneys ranked, in order of preference, the hearings they believed were best suited for

Zoom® as follows: non-evidentiary hearings (status and scheduling conferences, pretrials,

motions); traffic violations; civil infractions; summary proceedings; guardianships/

conservatorships; criminal pleas and sentencing; and short domestic relations evidentiary

hearings including pro confesso hearings.Moreover, these attorneys reported their clients appreciated Zoom® for the convenience and time savings from not having to travel to the court, park, and personally attend a hearing. Clients also expressed they were less intimidated by the process on Zoom® without losing respect for the procedure and decorum. The attorneys were less enthusiastic about evidentiary hearings involving multiple days, witnesses, and exhibits.

The attorneys expressed appreciation for the courts’ willingness to use Zoom® for motions, settlement conferences, scheduling conferences, status conferences, and limited evidentiary hearings. Incorporating Zoom® into the court process minimizes travel time, expense, and scheduling conflicts. The attorneys stated their clients anticipate Zoom® will be continued in the court system because it is a cost effective and efficient tool.

Trial courts reported Zoom® preferences similar to the attorneys. Circuit courts considered the following hearings the most beneficial for the Zoom® format: status and scheduling conferences, pretrials, motions, pleas and sentencing (provided the defendant consents to the hearing), PPO hearings (excluding those hearings where the respondent could be sentenced to jail), child protective and juvenile delinquency hearings (excluding removal hearings, parental termination, and juvenile trials), pro confesso hearings, and most domestic relations hearings that do not involve multiple days, witnesses, and exhibits.

District courts reported that Zoom® was preferred for pretrial and status conferences, traffic violations, civil infractions, probable cause hearings, landlord-tenant and summary proceedings, and pleas. Probate courts reported a broader acceptance of Zoom® because many hearings can be conducted within a day, such as estate petition and motion hearings, mental health hearings (except jury trials), and guardianship and conservatorship. At least one probate court reported conducting a jury trial by Zoom®.

Friends of the court also reported a general acceptance and efficiency associated with remote hearings and meetings. The majority of FOC offices expressed the convenience for parents to engage in meetings with the FOC investigator by Zoom®, reducing travel time and time from work without reducing the effectiveness of the meetings compared to in-person meetings. FOC has had to prepare instructions for parents to share documents prior to the meeting. FOC reports that parents have generally been supportive of remote meetings and hearings, although acknowledged an initial learning curve. FOC has also utilized Zoom® for mediation and dispute resolution with positive results

An unexpected finding from the use of Zoom® is that minors appearing before the court are more receptive to the hearing and less intimidated or anxious. Family division judges reported that in interviews to determine the reasonable preference of a minor child in a custody matter under MCL 722.23(i) and in juvenile delinquency proceedings, the minor children appeared more relaxed and open in their discussion with the judge or referee. While this finding is anecdotal, a significant number of judges suggested the remote hearing eliminates the intimidation or fear of appearing in court in a predominately adult setting. The video nature of the Zoom® proceedings may provide an experience the minor children are more comfortable with given their familiarity with video games and other digital interactions.

Data points like from these surveys were not mentioned when three Michigan jurists recently shared their personal opinion that virtual court hearings erode public trust.

And while their sentiment that “The in-person presence of judges, court staff, and attorneys is essential to the efficient functioning of the judiciary and upholding the credibility and professionalism of the legal profession. Virtual proceedings offer a false promise of convenience.” is an important one, it’s also important to remember how courts are not reliably physically accessible for everyone.

Pre-covid, trial courts in Hawaii and Alaska, for example, were successfully using telephonic hearings/trials by default because there is no routine drive/trip to the courthouse because of their geographic barriers. Such access-to-justice realties were detailed in the Joint Technology Committee’s Resource Bulletin Teleservices for Courts:

While some courts utilize telephones primarily to answer questions and direct callers to other resources, many courts hold hearings and even trials using information and communications technologies. Geography demands flexibility and practicality in many jurisdictions. In Hawaii, for example, parties may be located on different islands, necessitating air travel for in-person appearances. In some situations, parties can request telephone appearances. While these must be pre-approved by the court, telephone appearances are common and liberally granted for non-evidentiary hearings for neighbor island courts. Attorneys and parties are spared the cost and inconvenience of “island hopping” to attend court.

In Alaska, telephonic appearances are routine. Litigants, witnesses, clerks, and judges alike utilize telephones to conduct or participate in both hearings and trials. Depending on the court and the parties’ locations, the judge may include call-in information in scheduling orders. Parties also use fillable PDF forms available on the Alaska Court System website to request to appear by telephone if they are unable to come to court because of work conflicts, medical reasons, travel, lack of transportation, etc.

The individual requesting the telephone appearance provides a phone number and commits to be available for a two-hour window after the scheduled hearing time. The request form provides the courtroom’s unique 800-number and once approved, a secure call access number. Courtrooms are outfitted with audio systems that facilitate both amplification and recording. Audio recordings are the official record. When approved by the Alaska Supreme Court, appeals can refer to audio segments without the need for transcription.

If a party “fails to appear” (does not call in at the appointed time), it is common for the judge to pick up the phone and call the individual. This collaborative approach to justice reduces the incidence of continuances and promotes more efficient use of courtroom time to resolve matters before the court. Aside from the request that parties not be driving during court, individuals can participate in their hearings from any location that has landline or cellphone access.

Back to Michigan. At least since 2008, Michigan courts have been collaborating with the Michigan Department of Corrections and local jails to reduce prisoner transport costs through video appearances. This arrangement has saved taxpayers tens of millions of dollars over the years. There has never been a complaint about a loss in public trust. Michigan Supreme Court Justice David Viviano championed its success in 2015 explaining: “Videoconferencing is common sense technology that saves time and money. At the same time, not transporting prisoners reduces risk. That’s a win-win.”

Even earlier, back in 2001 (ish), Michigan Governor John Engler championed the creation of a “Cyber Court”. While authorizing legislation was signed into law, the project was never funded, and the related laws were later repealed in 2012. Importantly, it was a lack of funding and not a lack of public trust that derailed the effort.

There’s always room for improvement in making our courts accessible for all users.

When it comes to learning the pulse of the public’s trust about remote hearings, I’ll be eager to review NCSC’s 2024 survey results when they’re published later this year for any change in public sentiment or expectations about remote court hearings. I hope you will, too.