A Gwinnett County, Georgia court will handle what’s thought to be the first defamation lawsuit about a ChatGPT response (h/t Bloomberg Law and Professor Eugene Volokh).

The June 5, 2023 complaint is thin on important details about the non-party user’s ChatGPT exchanges (or any damages suffered by the named plaintiff who has a fairly common name: Mark Walters). (Hard to resist a term sometimes used by SCOTUS Justice Kagan).

I agree with Professor Volokh’s June 6, 2023 assessment that “this particular lawsuit should be hard to maintain.”

But recent suggestions shared in an unrelated case could be helpful as we navigate this new arena.

AI-pleading suggestions

The bench and bar may find to be helpful (my emphasis shown below) the pleading suggestions recently outlined in an amicus brief in an unrelated case (from the show-cause hearing where a New York City attorney blamed ChatGPT for the made-up legal research he included in court filings):

C. Use, evaluation, and perfection of chat transcripts as evidence.

The transcripts described above may be the first time in a US Court, federal or state, that work product consisting of text produced by generative artificial intelligence software, is being evaluated for evidentiary value. The more complete impression provided by the longer printed transcripts compared to the partial screenshots demonstrates the higher weight the Court should accord them. Evaluating partial screenshots of partial transcripts is analogous to providing a partial bank ledger or partial deposition testimony.

Perfected evidence of a Generative Artificial Intelligence chatbot would consist of an entire chat transcript, the name of the language model (eg, GPT-3.5, GPT-4), the name of the software application (ChatGPT, Bard, Poe, Bing, CoCounsel, Spellbook, CereBel) the date of production, and, in some instances, other parameters that could vary or otherwise been known (eg, temperature; completion length; presence, frequency or other penalties; top-p; etc.) Even then, not all chat transcripts can be recreated verbatim even when the chatbot configuration is replicated for a variety of reasons including small discrepancies in the operation of floating point numbers.

Thoughts from the APA Style team on How to cite ChatGPT

Quoting ChatGPT’s text from a chat session is therefore more like sharing an algorithm’s output; thus, credit the author of the algorithm with a reference list entry and the corresponding in-text citation.

Example:

When prompted with “Is the left brain right brain divide real or a metaphor?” the ChatGPT-generated text indicated that although the two brain hemispheres are somewhat specialized, “the notation that people can be characterized as ‘left-brained’ or ‘right-brained’ is considered to be an oversimplification and a popular myth” (OpenAI, 2023).

Reference

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

You may also put the full text of long responses from ChatGPT in an appendix . . . .

The Gwinnett County, Georgia case allegations

The Gwinnett County, Georgia lawsuit is not a model for pleading allegations involving generative AI:

9. On May 4, 2023, Riehl interacted with ChatGPT about a lawsuit (the “Lawsuit”) that Riehl was reporting on.

10. The Lawsuit is in federal court in the Western District of Washington, case No. 2-23-cv-00647, with short caption of The Second Amendment Foundation v. Robert Ferguson.

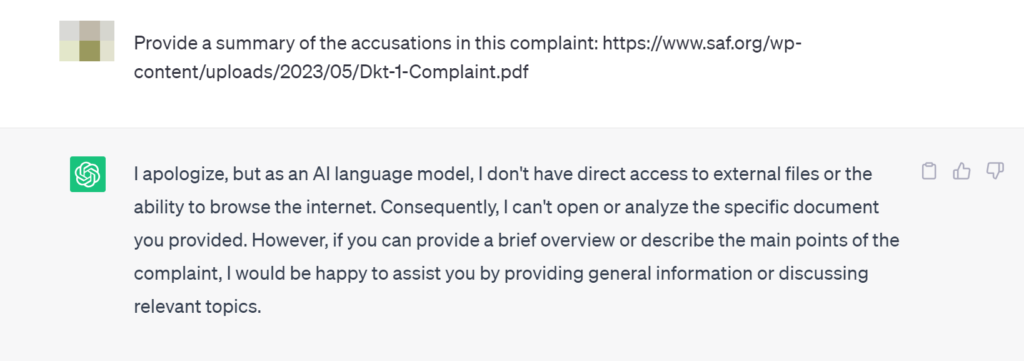

14. In the interaction with ChatGPT, Riehl provided a (correct) URL of a link to the [May 3, 2023] complaint on the Second Amendment Foundation’s web site, https://www.saf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Dkt-1-Complaint.pdf.

15. Riehl asked ChatGPT to provide a summary of the accusations in the complaint.

The GA lawsuit’s missing chat-exchange details will probably matter (a lot!); bigger-picture facts that should be considered:

ChatGPT works from data current through 2021—not 2023 (when the Second Amendment Foundation lawsuit was filed in federal court in Washington state). What this means is that, at first blush, ChatGPT was the wrong tool for what the reporter tried to do.

Plus, at the time of the Gwinnett County, Georgia lawsuit’s alleged May 4, 2023 exchange, ChatGPT did not have any internet access and so could not summarize content behind any URL link listed in a prompt (in the way suggested by paragraph 14). So, here, it becomes key to understand: What—exactly—did the non-party prompt to ChatGPT, and what form of ChatGPT was being used?

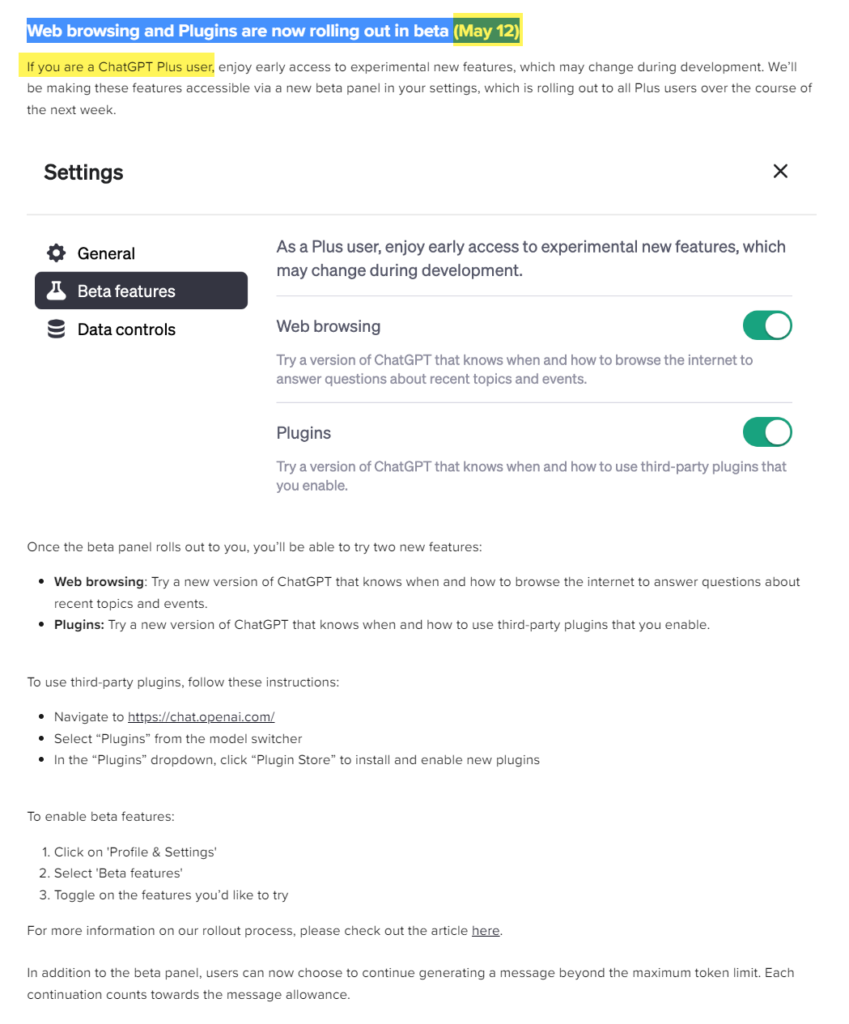

In fact, ChatGPT didn’t start a limited release of its web browsing feature for ChatGPT Plus users until later (May 12 according to OpenAI’s release notes).

FWIW (probably not much), I am not a ChatGPT Plus user and, on June 9, I could not replicate the ChatGPT exchange described in the Gwinnett County, Georgia complaint about the federal lawsuit pending in Washington state. ChatGPT explained that it could not respond to my prompt because ChatGPT did not have internet access and could not open or analyze the linked URL document.

But see how the Gwinnett County, Georgia lawsuit, as alleged, doesn’t give us more to work from to assess what happened and how?

Of separate important note, the Gwinnett County, Georgia lawsuit does not claim that the non-party user, Fred Riehl, used any type of ChatGPT plugin that allows users to feed PDFs into ChatGPT (like, for example, https://askyourpdf.com/).

Just for fun, I uploaded the https://www.saf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Dkt-1-Complaint.pdf link to https://askyourpdf.com/

I asked it to read and summarize the file.

Askyourpdf.com did not mention the plaintiff’s name in the Gwinnett County, Georgia lawsuit.

So I specifically asked, “Tell me what allegations concern Mark Walters”.

The tool responded that “There is no mention of Mark Walters in the provided context.”

[I had a similar “no hit” experience on June 10 using ChatPDF.com]

So, again, I am lost at how to construe the Georgia defamation lawsuit in any light most favorable to the plaintiff Mark Walters.

Bottom (pleading) line

In the litigation space, it would help to plead and look for elements like:

- entire chat transcript, the name of the language model (eg, GPT-3.5, GPT-4),

- the name of the software application (ChatGPT, Bard, Poe, Bing, CoCounsel, Spellbook, CereBel),

- the date of production, and,

- in some instances, other parameters that could vary or otherwise been known (eg, temperature; completion length; presence, frequency or other penalties; top-p; etc.)

Damages can be an important consideration and, again, I don’t know how this Gwinnett County, Georgia lawsuit plaintiff will show any demanded damages to any future jury. (The website Spokeo, for example, returns 60 Georgia listings for the common name “Mark Walters”.)

First, it does not seem that the statements can be reproduced in the manner alleged so there should not be a risk of re-publication to the public.

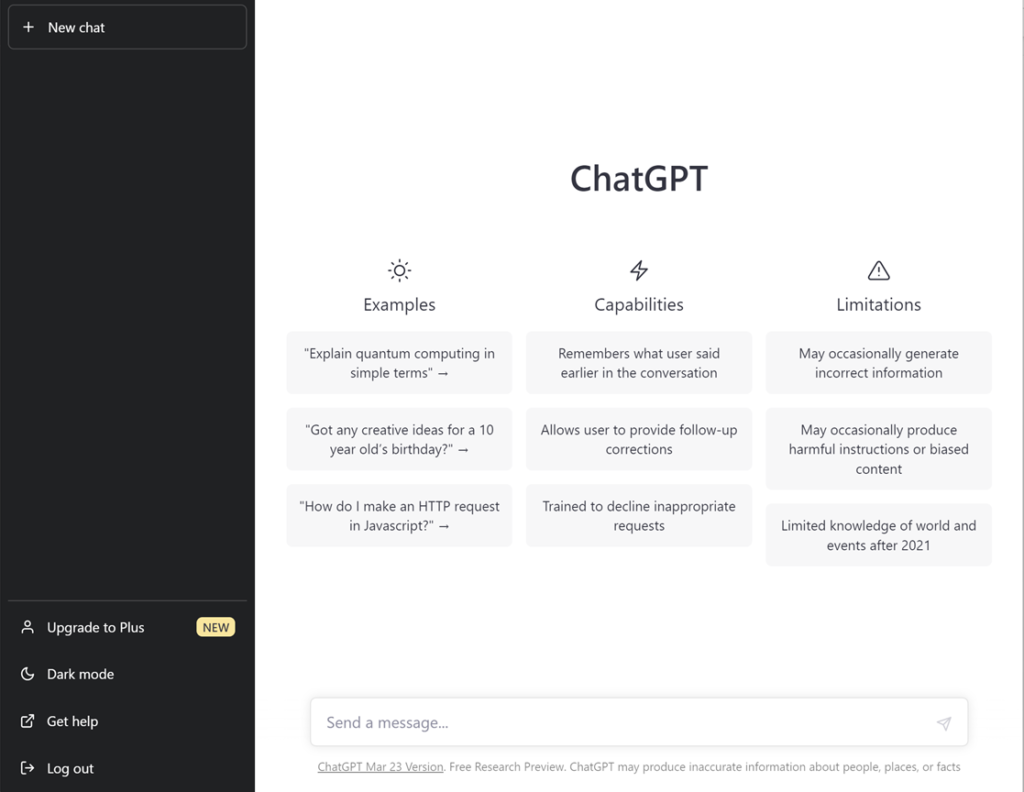

Second, it seems that any “statements” were limited to Fred Riehl—who promptly reached out to others and learned the characterizations were false. To me, this means that there is no claim that Fred Riehl (or others) believed or relied on the alleged ChatGPT response—a response where users are regularly reminded that the information is sometimes incorrect and limited, and that “ChatGPT may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts.”

Let’s give the lawsuit a closer look. The Gwinnett County, Georgia plaintiff does not specify any harm to him or his reputation by any alleged one-off ChatGPT response. His lawsuit simply demands:

- General damages in an amount to be determined at trial.

- Punitive damages in an amount to be determined at trial.

- The costs of bringing and maintaining this action, including reasonable attorney’s fees.

- A jury to try this case.

- Any other relief the court deems proper.

Should that be enough to put defendants on notice? Or will courts (and juries) require more?

Update: New example

OpenAI, Inc. (ChatGPT) was sued in federal court on June 28, 2023. Exhibit B to the complaint is 11 pages of the prompts and output which are the focus of the suit. It is an example to keep in mind!