Folks write and (e)file their own court papers in civil and criminal cases each day.

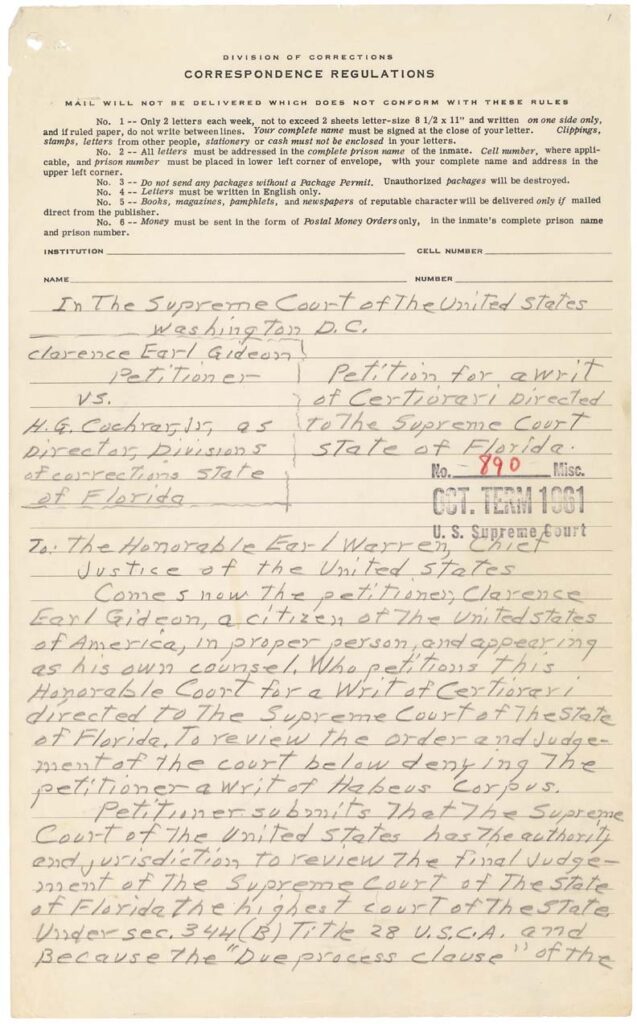

Ordinary people—like Clarence Earl Gideon (handwritten in pencil) and Steven Alan Levin (formatted in Microsoft Word)—have successfully petitioned the Supreme Court of the United States on their own.

The Michigan Supreme Court ordered oral argument on two handwritten applications filed by self-represented persons during its 2020-21 term. (Hughes – 158652 and Stock – 160968)

And, throughout the years, the Michigan Supreme Court has received and considered amicus (friend of the court) briefs filed by individuals. Sometimes they’re typed. (Manning in 160034 and Cyars in 153828). Other times, not. (Rowe in 160707 and Miles-El in 160034).

While courts do the best they can in processing and deciding these filings, sometimes the self-prepared filings are hard to understand. It’s easy to lose when the judge does not understand what the person is trying to say or what they’re asking for.

The facts that plaintiff relies on are intertwined with his legal allegations and are difficult to comprehend. Furthermore, the complaint does not reasonably inform defendant of the nature of the claims against it. The complaint is vague, overly long to the point of excess, and contains confusing syntax and grammar. Plaintiff also fails to state in an understandable manner what he is alleging or how he supports his claims. The complaint consists mainly of incoherent ramblings, interspersed with legal jargon, resulting in allegations that are not clear, concise, or direct. See MCR 2.111(A)(1). Relying solely on the complaint, we are unable to discern what plaintiff seeks to gain from this lawsuit.

Woods v. SLB Property Management, LLC, 277 Mich App 622, 627-28 (2008)

Many of these problems can be avoided with the benefit of time to write thoughtfully. (This is also true for when lawyers and judges write things.) Time to think about what you want to say and how you want to say it. Time to draft. Time to edit. Time to re-write, if necessary.

Matthew Butterick best explained why you want to be respectful of your reader’s (judge’s) attention with what you write:

Attention is the reader’s gift to you. That gift is precious. It is finite. And if you fail to be a respectful steward of that gift, it will be revoked.

Once your reader revokes the gift of attention, you’ve achieved only the lowest form of writing. Yes, you scattered some words across some pages. But your reader disappeared. So what was the point? Your writing might as well be a random string of characters. Like the proverbial tree falling in the woods, no one’s there to notice the difference.

Nevertheless, many legal writers adopt a high-risk model of reader attention. Instead of treating reader attention as precious, they treat it as an unlimited resource. “I’ll take as much attention as I need, and if I want more, I’ll take that too.”

What could be more presumptuous? Or dangerous?

Writing as if you have unlimited reader attention is presumptuous because readers aren’t doing you a favor. Reading your writing is not their hobby. It’s their job. And their job involves paying attention to lots of other writing. Your judge has not set aside your motion for summary judgment so she can savor it during her upcoming vacation to Maui. More likely, it’s just one document in a pile of hundreds, all competing for her attention.

I’ll even go one better: I believe that most readers are looking for reasons to stop reading. Not because they’re malicious or aloof. They’re just being efficient. Readers who have other demands on their time—meaning, all of them—can’t afford to pay more attention than necessary. Thus, they’re always looking for the exit. Though legal writers routinely ignore this fact, they do so at their peril.

Writing as if you have unlimited reader attention is also dangerous, because running out of reader attention is fatal to your writing. The goal of legal writing is persuasion. Attention is a prerequisite for persuasion. Once the reader’s attention expires, you have no chance to persuade. You’re just giving a monologue in an empty theater.

So please plan to give yourself time if you will be writing to the court on your case. And here’s a list of other considerations to help you put your best words forward.

[1] Find and read the current court rules for current requirements. Standards change. That old example someone shared that you’re working from may not follow the current rules. It’s frustrating to have a filing rejected because it does not follow the current rules.

[2] No matter if it’s handwritten or typed, keep the text large with a fair amount of white space so your audience can read it.

[3] Use black ink if handwriting. Blue ink does not always scan well when your paper filing is digitized. Neatness matters. Print if you can. Not everyone knows how to read cursive.

[4] Stay away from “legalese” or words that do not help tell your side of things or persuade the judge why she should approve what you are asking for. Don’t simply dump a kitchen sink of court case names or statute or court rule numbers. The court will not do your work for you.

[5] Tell the court what you want it to do. Make sure that the judge has the authority (by law or court rule) to do it. In writing The Presentation Secrets of Steve Jobs, Carmine Gallo suggested a perspective that is also true of judges. “The listeners in your audience are asking themselves one question: ‘Why should I care?’ Answering that one question right out of the gate will grab people’s attention and keep them engaged.”

[6] Avoid personality attacks. Leave out the anger and frustration you may have about the judge, police, prosecutors, witnesses, ex-partners, and the like. Your feelings may be valid. But they won’t help persuade the judge to decide in your favor.

[7] Number your pages and list your case file number.

[8] Include your current contact information. Let the court know of any changes.

[9] Use a link-shortener (like bitly.com) if including internet hyperlinks. This is especially helpful if your filing is handwritten.

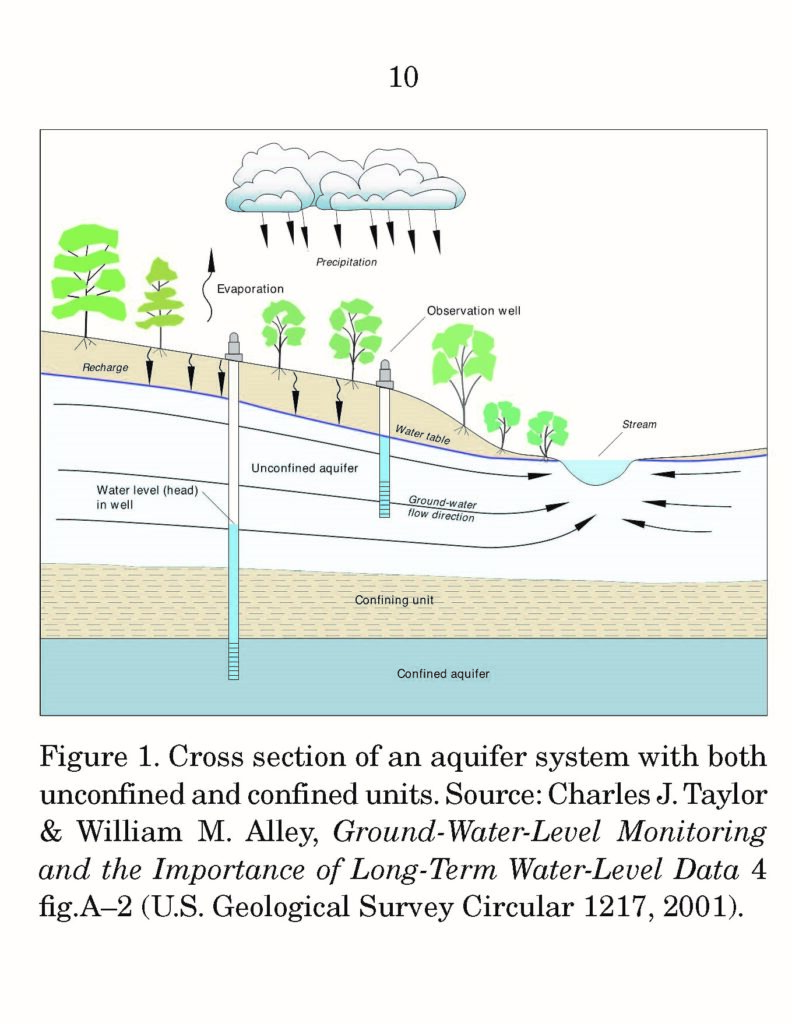

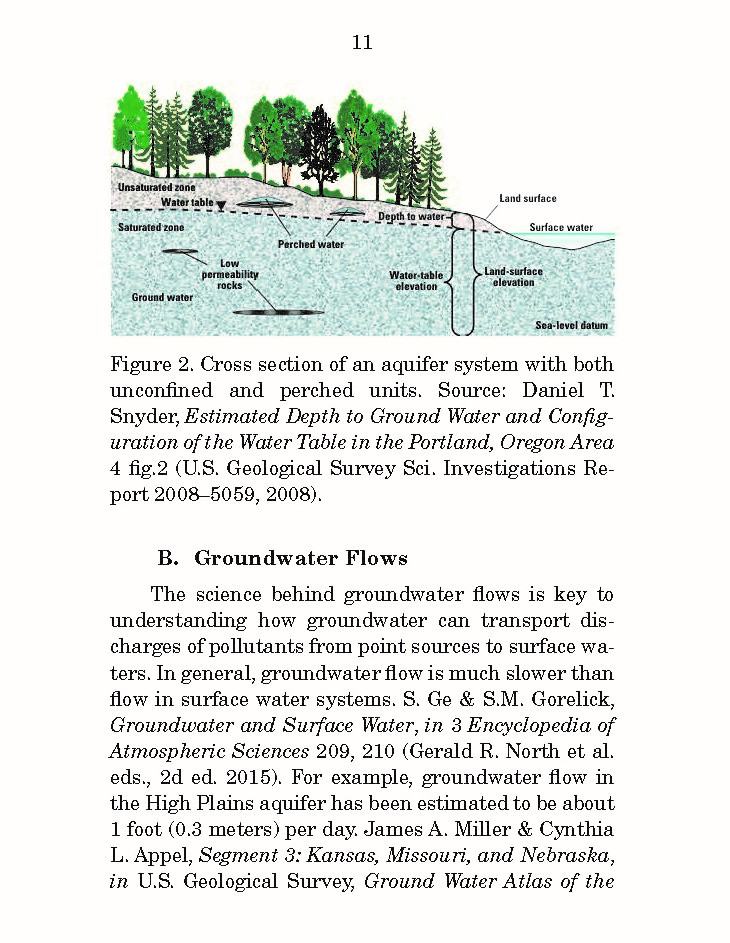

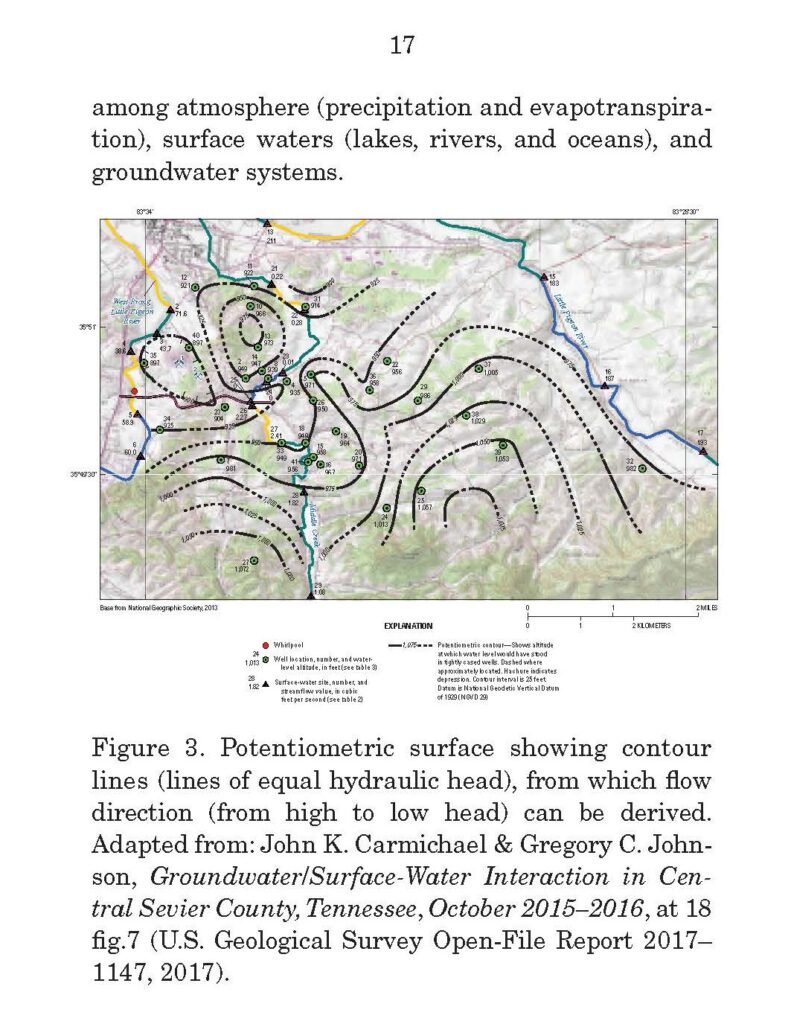

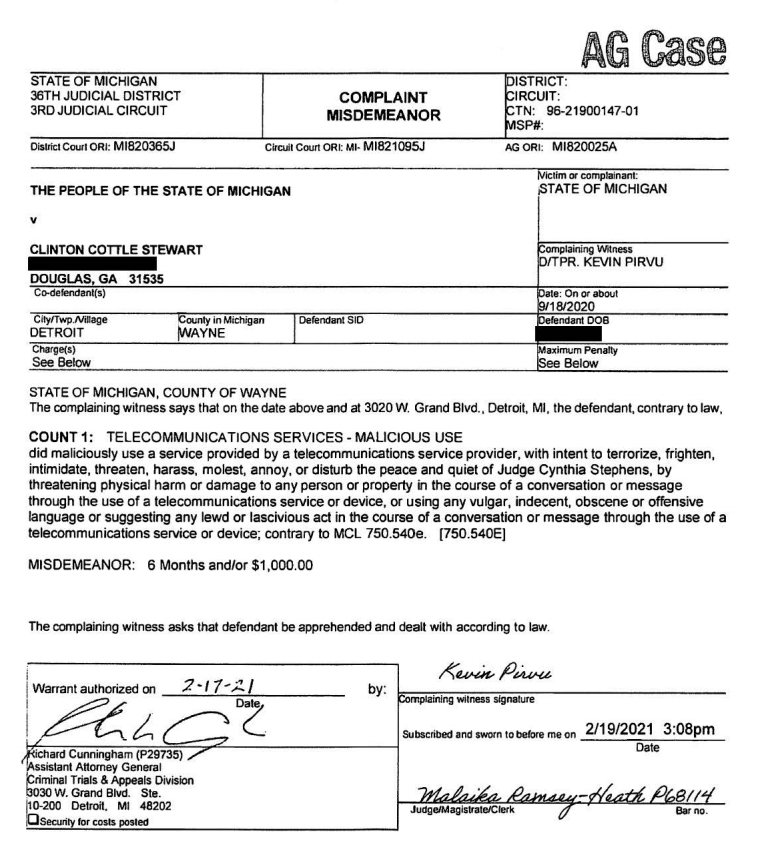

[10] Label and explain any pictures and images. What are they, why are they important, and where are they from? If you want them to be part of the record and be considered, you have to include the “legal foundation.” Here’s an example from a brief filed in the Supreme Court of the United States.

[11] If including transcript pages, use one page per sheet (not the kind that squish four pages onto one sheet).

[12] Go easy on any underlining and all-caps. That can become very distracting. Don’t overdo it. You’ll be fine with simple italics, actually.

[13] Redact (blackout) personal identifying information such as social security numbers, dates of birth, bank account numbers, and the like unless you must give them to the court unredacted. The importance of data privacy in legal writing redacting and data privacy was explained in this post.

[14] If using a computer to type your pleadings, use spell check. And know how to correctly spell any judges’ names that you include. Justices and judges notice when their name is misspelled (just like you do when someone does it to yours). Here’s a separate post where I show how to review and adjust your Word grammar and spell-check settings.

[15] Avoid ex-parte letters or filings. Whatever you send to the court, also send it to the other parties.

Interested in other writing tips?

There’s a legal writing section in The Canadian Judicial Council’s Family Law Handbook at pages 79-82. Don’t be distracted by the title. Their helpful suggestions apply to all court filings.