Why? Because many third-party-online publishers leave images out from the original decision.

Imagine footnotes like these being dropped into a judicial decision:

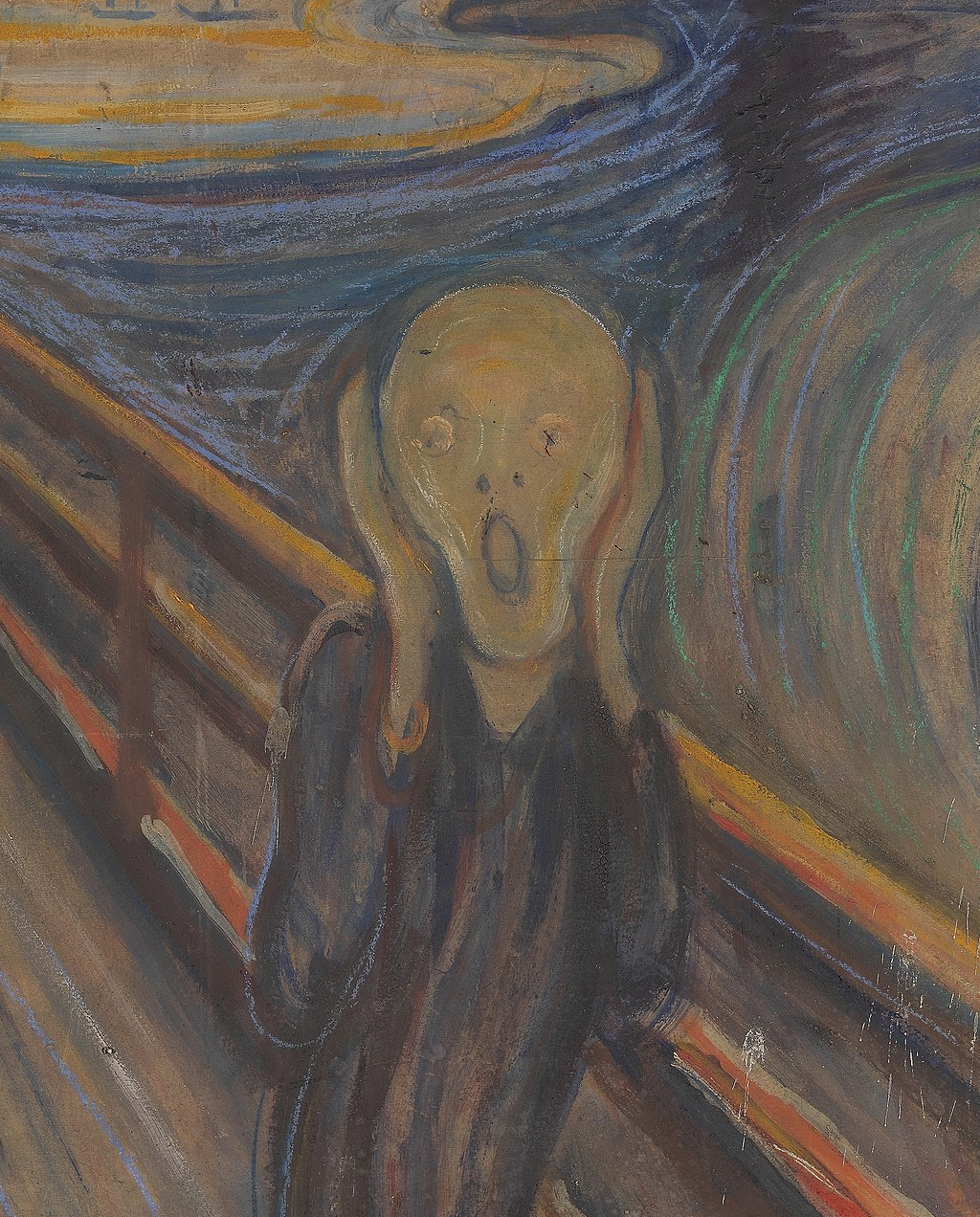

[Proposed new footnote:] To help future readers who may read this decision in a third-party, text-only format that left out the image, Figure 1 is a black-and-white portrait photograph of Prince taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith.

[Proposed new footnote:] To help future readers who may read this decision in a third-party, text-only format that left out the image, Figure 2 is a purple silkscreen portrait of Prince created in 1984 by Andy Warhol to illustrate an article in Vanity Fair.

The problem: The “disappearing” opinion images (and sometimes image captions) by third-party-online publishers

Around 16 images were added to and substantively discussed in the majority and dissent opinions as released in SCOTUS’s 87-page .pdf file in Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. ___ (2023).

Many third-party online publishers—however and to the surprise of many—often drop any images included in the original court opinion. Really!

What it means: The many images readers “see” in the SCOTUS-released version, they “don’t get” when reading the online version published by media like Google Scholar, Legal Information Institute, Justia, and others. Like the others, Casetext did not include the images but, to its credit, Casetext (1) tells the reader that “(Image Omitted)” and (2) includes the written figure caption.

| How it started (original) | How it’s going (Google Scholar, Legal Information Institute, Justia) |

| Justice Sotomayor’s majority opinion included labels and brief caption descriptions for her 8 images. | None of the Sotomayor images or captions were carried over to Google Scholar, Legal Information Institute, or Justia’s .html republished versions. Casetext tells the reader when an image was omitted and still includes the image’s written caption. |

| Justice Kagan did not assign any figure numbers and did not always include a caption description for the 8 images she included in her dissent. | No Kagan-included images appear in Google Scholar, Legal Information Institute, or Justia’s .html republished versions. (Somehow, however, some of the unnumbered captions are republished.) ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Casetext tells the reader when an image was omitted and still includes the image’s written caption if Justice Kagan included one. |

Zoom in: Here are the side-by-side comparisons of the original SCOTUS-pdf against Justia’s online version with my annotations.

Reality check: Because this SCOTUS decision is substantively about images, the images’ inclusion cannot be discounted as simply “decorative.” The contrary must also be true: the images’ omission by third-party online publishers cannot be overlooked as inconsequential.

Zoom out: What to do and that will work?

Thoughts and suggestions

Image treatment, part 1: Number the images (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.) and include descriptive text

“When we use an image in our work, it is our job to describe in text what the image contains—in the way most contextually relevant to where it appears—for blind and low-vision users.” The Washington Post, design system accessibility resources.

Justice Sotomayor’s opinion shows the helpfulness with assigning a “Figure” number and description for each image in her decision. Through the descriptive text, one “tells” what they want to make sure is shown by the image record.

The Modern Language Association (MLA) format for citing images [Artist last name, First name. Piece name. Year, location.] is different from including helpful, descriptive text.

Chapter 7 of the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Publication Manual has the gold-standard guidance for numbering, titling, and describing included images (often called “figures”).

The Washington Post and the National Gallery of Art also share helpful suggestions for drafting image text descriptions.

The descriptive text does not have to be complicated, depending on the circumstances. The U.S. Attorney included short, descriptive labels for the four photograph figures included in this memorandum. (Figure 1 – Photograph of Firearm Taken by Witness 1. Figure 2 – Black Laser Sight. Figure 3 – Recovered Ammunition and Magazine Drum. Figure 4 – Firearm with Rifle Converter)

Image treatment, part 2: “Footnote” the descriptive text.

To work around the chance of third-party-online publishers dropping both the image and its caption (like what often happened in Justice Sotomayor’s opinion), the Justice could have dropped a footnote in the body text when she referred to the figures. For example:

[Proposed new footnote:] To help future readers who may read this decision in a third-party, text-only format that left out the image, Figure 1 is a black-and-white portrait photograph of Prince taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith.

Image treatment, part 3: Add an itemized Appendix of the Figures with their descriptive text at the end.

The footnote approach at every time a figure/image is referenced would get clunky when one image is cited several times in an opinion (or companion concurrence, dissent, etc.). And that is what happened in Warhol.

To avoid clunky, it should only be necessary to footnote the image the first time it is referenced. And at the end of the decision, the judicial author can include an itemized, text-only Appendix that lists each Figure with the descriptive caption. See how that Appendix could become an easy go-to reference for readers?

Working from the first seven numbered Figures in Justice Sotomayor’s Warhol opinion it would look like this:

Figure 1. A black and white portrait photograph of Prince taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith.

Figure 2. A purple silkscreen portrait of Prince created in 1984 by Andy Warhol to illustrate an article in Vanity Fair.

Figure 3. An orange silkscreen portrait of Prince on the cover of a special edition magazine published in 2016 by Condé Nast.

Figure 4. One of Lynn Goldsmith’s photographs of Prince on the cover of Musician magazine.

Figure 5. Four special edition magazines commemorating Prince after he died in 2016.

Figure 6. Warhol’s orange silkscreen portrait of Prince superimposed on Goldsmith’s portrait photograph.

Figure 7. A print based on the Campbell’s soup can, one of Warhol’s works that replicates a copyrighted advertising logo.

[N.b., I am stopping at this point because—again and most unfortunately—Justice Kagan did not assign any figure numbers and did not always include a caption description for the 8 images she included.]

Has anyone done some form of the footnote-appendix approach before?

Yes! While she did not include “Figure X” labels, Justice Ginsburg employed this approach in her American Legion v. American Humanist Ass’n, 588 U.S. __ (2019) dissent.

And, importantly, RBG’s footnotes and the text portions of her Appendix entries, carried over to the third-party case online publications, like Justia.

Justice Ginsburg understood.